In early 1999, I was living in India when I was pregnant with my son, who is now twenty-five. Before returning to the U.S., I went out looking for books to bring home for the baby still yet to arrive. In Delhi, I happened on A Visit to the City Market, by Manjula Padmanabhan and published by the National Book Trust of India.

It’s a book without words that tells the story of a brother and sister running errands with their mother. Entering the moment of each page over and over, I was mesmerized, like a little kid, memorizing every piece of okra and every shade and shape of every mango. I hadn’t wanted to leave India and the book, which ended up being more for me at the time than for the baby, became somewhere I could linger. Just like in a real market, there was so much to take in! I read it so many times with both of my kids, I eventually had to re-staple the cover.

Though it’s been two and a half decades since I first encountered A Visit to the City Market, I still think about, especially now, seeing the images and interactions captured in the book in the markets around Kolkata and vice-versa, a reminder of the importance of books that both expand our sense of the world and that reflect back at us the richness of our own.

I was also recently reminded of my love for A Visit To the City Market as I learned more about how the field of Indian literature for children has grown in recent years. Since 2005, Parag Reads has been committed to nurturing the children's literature sector across India. The organization works with publishers, authors, illustrators, libraries, library educators, and others to make books more accessible to children, both financially and in terms of the language and content. Last week, I sat down with Proma Basu Roy to talk about her work for the organization and why even picture books without words should reflect different languages. [The following conversation has been edited for length & clarity.]

Can you tell us a little bit more about Parag’s mission?

Parag has always believed in the transformative power of reading, and all our work is driven towards that. The mission has been to make good books available and accessible to children.

While there has always been children’s literature in regional languages, which is a very rich body of work, especially in states like West Bengal, Kerala, Maharashtra, and Karnataka, to name a few, these books have traditionally been text heavy and only really accessible to children who already had good hold on the 'reading' ability.

In a way, there’s a logic to this: India is a culture of oral histories, of folklore, of stories that are told, so the role of pictures was not there. But that also meant there was not much for early readers in India in terms of picture books.

And, in a country that is so stratified and so diverse, there was previously a felt dearth of reading material that was contemporary and that represented different groups of society. But in children’s literature, you want to include all children and you want to make the content relevant. You wouldn’t want to talk about cheese and a cup of coffee to a child in rural Karnataka or rural West Bengal. It would make no sense.

Parag, along with the effort of so many publishers, authors, illustrators and translators, has been able to shift that periphery and broaden it. Now there are both profit and non-profit publishers that do great books and that represent diversity. In hindsight, I see the contribution of the organization and that it has been able to stretch the boundary of the imagination for children’s literature.

What does your role include?

I lead the Big Little Book Award, which recognizes and honors authors and illustrators of children's literature in India. I also lead Parag's participation in IBBY (International Board of Books for Young People), which is a network of 85 countries. Being a part of IBBY gives us the opportunity to take Indian children's literature to a global platform while bringing home best practices around literature and reading programs.

In the past, I also worked on a library program in Gadchiroli, in rural Maharashtra, where we set up libraries from scratch in 50 government schools and provided support to the teachers there for running the libraries.

In September, Parag also facilitated a fabulous masterclass, in Bhopal, a workshop on creating wordless stories with twenty illustrators from around India, representing a range of regions and languages. It was an effort to bring a focus to that genre, especially in the regional languages.

I love thinking about the importance of diversity of language in books that don’t have any words at all.

It’s the thought language that gets represented. An illustrator who comes from, say, Tamil Nadu will have an imagination of one kind and an illustrator from Assam will have an imagination of another kind, but they all communicate so beautifully to the reader. Such is the power of pictures, of illustrations.

Picture books are also expensive; they require full color. So, regional language publishers have to spend a larger amount than for books with only text. That’s a challenge. For parents as well there’s a challenge. We are so used to reading being synonymous with reading text, so it’s a question of how to introduce the idea that children read pictures before they read texts. Children draw before writing. They see before speaking. That’s where the journey of learning begins, by which I mean nothing about a formal education, but I mean learning about the world.

Can you say more about what it means to establish libraries in rural areas - both practically and in terms of the impact?

Tata Trusts runs libraries through their associate organizations, and Parag offers technical support for setting up and running the libraries (with things like) putting together lists of carefully selected books in different languages. This happens in eight states, and it’s a different list in every state. We also ensure capacity-building for those who run the libraries. Most of the schools have limited resources, and we want to ensure the experience of joyful reading to whatever extent possible. Some schools have a classroom-corner library, while some have an exclusive library room.

In Maharashtra, in the Gadchiroli district, I went around, along with other team members, identifying schools for our library program, checking for rooms where libraries would be possible. It was like searching for a beginning.

After four years, schools that had previously had no libraries and no books went to having book clubs. Many of these teachers had never seen picture books before. But we established libraries in 50 schools, and these were government schools, so the teachers will be transferred, and I’m hopeful that these teachers will carry this experience with them.

As part of the collection, we put in Hana’s Suitcase – the book is available in Marathi. Many of these teachers spent weeks on this book with the children and moved to doing activities with them about treasured things that have been lost. This project has been phenomenal.

Have you had any recent conversations about books that were surprising or unexpected?

Yesterday I was couriering a set of books to IBBY Italy – all Indian books. The two men who were doing the courier said to me, “Ma’am you are sending foreign books back to foreign?” I said these are not foreign books. These are Indian books. But they noticed that the production quality of the books was so fantastic and yet so inexpensive – and we got to chatting about these books.

I don’t think it’s fair to ask someone if they have a favorite book. Instead, I’ll ask what picture books would you like to share with readers inside and outside India?

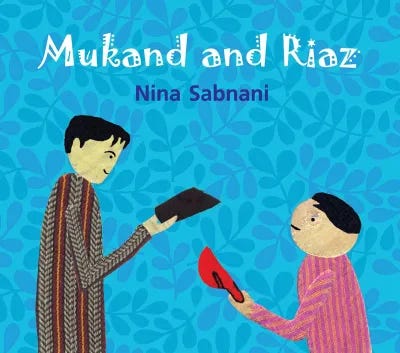

One of my top favorites is Mukand and Riaz, by Nina Sabnani, which is available in many languages and published by Tulika Books. It tells her father’s story; her father was the Mukand of Mukand and Riaz, friends who were separated during Partition when Mukand had to leave (what is now) Pakistan and come to Bombay. She illustrated it with needle and thread.

I have worked extensively with children on this book. We spent a whole month on it, in a community of migrated children from Uttar Pradesh and Bihar, because this is also a book on migration. The children might not have migrated; they are second generation, but their families migrated. We did interviews. We made questions together that the children asked their parents, their grandparents, and their neighbors. Then we made a book on friendship, together, where every page they made a collage. This was in a community where needlework is a big part of the craft and livelihood at home, and one of the children said that she didn’t want to do a collage, but rather to use needle and thread, just like in the book.

This is a very special book. This books comes with so much history - the experience of so many people and of generations. It is especially meaningful because my mother’s side came from East Bengal (now Bangladesh) during Partition. My father’s side moved to Burma and then came to India. Mukand and Riaz separated in 1947 and so did my mother’s family. This is the story of so many people in India, and that's how we remain, in stories.

Other recommendations from Proma include:

Mahagiri by Hemalata

Treasures from Tibet written and illustrated by Malavika Navale

Busy Ants by Pulak Biswas

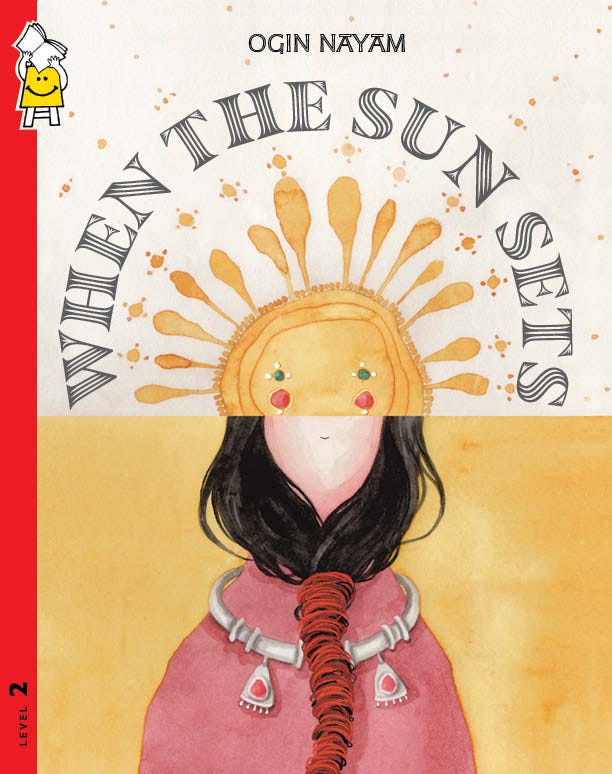

When the Sun Sets written and illustrated by Ogin Nayam